ARTIST's STATEMENT

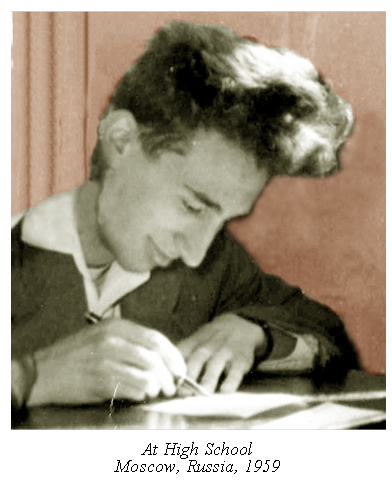

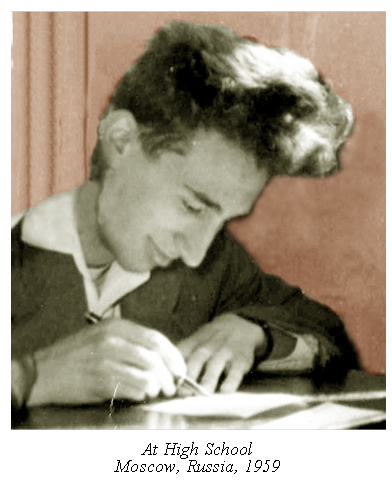

I first began painting in the late ’50s of the last century.

This was during the period of nonconformist art in Soviet

Russia. I think perhaps the starting point of this movement was the VI

World Festival of Youth and Students, which took place in Moscow in the summer

of 1957. It was held under the slogan “For peace and friendship” and obviously

had a propagandistic character, which met the objectives of the communist

regime. Still, it had many positive moments. Soviet executive bodies, confused

and distracted by conflicting movements in the upper echelons of power, failed

to monitor events to the usual degree. So during two weeks of that summer,

Moscow was full of unusual excitement. Things that had seemed absolutely

impossible only a couple of months earlier became reality in the Moscow

streets. Ordinary Soviet people were able to meet foreigners and talk with them

freely. And none of them were pursued for it. Well, of course they could only

talk by gesturing and gesticulating rather than actually speaking. Because in

those days, no one in Moscow spoke any language other than Russian. Moscow

girls actually felt no handicap on that count and went for it full-throttle. The

guys also managed not to get too hung up on linguistics, primarily because all

they were interested in were badges. A young man whose entire chest was covered

in badges was quite a common occurrence at the time.

Picasso’s “Dove of Peace,” although invented for another

occasion, became the symbol of the festival, and Picasso’s name thus became

known to a wider audience. During the festival, there were many exhibitions by

international artists. At these exhibitions, Muscovites were able to see

abstract paintings. That exposure was the impetus for creating their own

nonfigurative works, the style of which was strikingly different from the

socialist realism style prevalent at the time.

I was living in Moscow and happened to be spending the summer

break of 1957 in the city. The struggle for peace, as the theme was deemed by

the communists, was the key point of the festival. But the people of Moscow, it

seemed to me, did not pay much attention to it, especially because the hysteria

of that struggle was, in truth, not particularly intense at that point. All

this struggling for peace was not pushed by the Soviets to full capacity. They

were capable of much more. But at that moment, they were a little more relaxed.

For this reason, the festival, with all its exhibitions and its spirit of

relative freedom, had a positive impact on me and on many others as well.

Was I one of the nonconformists when I started painting? Well,

if I were to answer this question considering only the style of painting, then

I could be counted among the nonconformists of the period. However, I think it

is not enough to consider the painting style alone. The important

characteristics of nonconformism at the time were, first and foremost, the

artist’s lifestyle, and secondly, the nature of his relationship with the

Soviet authorities.

In other words, to be called a nonconformist, it was, first,

necessary to be part of the local bohemia or, at a minimum, to lead a lifestyle

close to bohemian. In addition, painting had to be the most important thing in life

or at least one of the most important things. Furthermore, it was necessary to

be in a state of minor but permanent, and perhaps most importantly,

intentionally open conflict with the authorities.

None of that applied to me at the time. From the mid-50s, I had

become more and more interested in mathematics. During my last four years in

high school, I was taking advanced math classes at Moscow University. At this

point, I was thinking long and hard about what I wanted to become. My father

advised me to get into math. He said it would be especially useful if I ever

ended up moving to America.

It was obvious that humanities were not my cup of tea. Choosing

to study history or literature in a totalitarian country did not seem like the

right thing to do. I did feel a kind of attraction towards music and visual

arts. But I already knew that the standard of living of, say, an ordinary

musician was not comparable to the standard of living of an ordinary engineer,

either in my country or, as rumor had it, in America.

All this made me lean in favor of pursuing exact sciences. Even

though, I understood that the Soviets could easily politicize exact sciences

just as well. One time our physics teacher, whom we had nick-named “Pike,”

announced that they had decided not to use the metric system in America. “How

come?” asked one of the guys. “In order to help the rich confuse the ordinary

people and make their life more difficult,” replied Pike.

Nevertheless, the choice of exact sciences was an obvious one

to me. Of all of them, only mathematics was not related to any kind of a

material base. Given the rotten state of the Soviet economy, this was quite a

significant point. And so that’s how I ended up

choosing mathematics.

My life in Russia could have gone in various directions. But in

1959, when I was graduating from high school, the Soviets experienced some sort

of a glitch and for some reason, the strict university admission quotas ceased

to apply. As a result, I, along with the other advanced math class members who

had Jewish surnames, became students at the Mechanics and Mathematics

Department of Moscow University. So nothing disorderly was expected to occur in

my life from this point forward. On the contrary, I already had a pretty

accurate idea of what I wanted to do in the future and how I would go about it.

And other than a standard scientific career, I didn’t spare many thoughts for

anything else. Therefore, without a doubt, I did not belong to the local

bohemia.

Was I in conflict with the Soviet authorities? Of course, I

was. To a large extent, this was the result of my father’s not hiding his

attitude towards the Soviets from me. Once he told me he had no doubt that one

day I would get the offer to join the Communist Party. And that he knew many

people who, without believing in any commie rubbish, still became party

members. They did it purely out of careerist considerations. “So here’s the

thing, my dear son,” said my father. “I implore you, never, ever have anything

to do with those bandits.”

At some point, my father was fired from his job and was on the

verge of becoming the victim of physical retribution. What saved him and

consequently our entire family was March 1953. However, the Soviets did not

deal the first blow to me personally until the summer of ‘59. Based on the

results of the main national math competition – The Moscow State University

Mathematics Olympiad – I was recommended for inclusion in the Soviet team as a

participant in the first international math Olympiad for high school students,

which was to be held in Romania that year. However, that’s where the KGB got

involved in the event. As a result, neither I nor any of the team’s members

with Jewish surnames were allowed to attend the international contest. And the

national Soviet team was only half-manned: instead of eight participants, only

four ended up going to Romania. Was I traumatized by this turn of events?

Certainly. But not very. After all, I had been accepted to a university and in

five years would be the holder of a degree in mathematics. This helped me to

forget the upsetting events that had just transpired.

Of course, I was in permanent disagreement with the

existing regime of the country. But only people close to me were aware of this.

None of us had either the ability or the desire to fight actively against the

political establishment. That struggle seemed to us to be very dangerous,

completely futile, and certainly not likely to lead to any attainable goal in

the foreseeable future. To be willing to engage in such struggle, one needed to

have special courage, which neither I nor any of my close friends possessed.

Besides, it seemed the existing social order, maybe with a few corrections, was

sufficiently suitable to the majority of the population. For this reason, all I

could think about was how to escape from the country.

My only open conflict with the Soviet system was linked to my

tendency to always keep smiling. This was despite an unwritten rule in Soviet

Russia: “Nobody smiles.” If you smiled, you perplexed ordinary Soviet citizens

and caused open irritation among those who stood above you on the ladder of

Soviet society. In high school, I was constantly scolded for smiling. The

phrase “What's so funny?” was perpetually hurled in my direction. The school

principal once went as far as to say, looking straight at me, “Some people have

ceased to look human because things are always funny to them.” Similar

scenarios pursued me at the university and elsewhere throughout my life in

Soviet Russia.

My only open conflict with the Soviet system was linked to my

tendency to always keep smiling. This was despite an unwritten rule in Soviet

Russia: “Nobody smiles.” If you smiled, you perplexed ordinary Soviet citizens

and caused open irritation among those who stood above you on the ladder of

Soviet society. In high school, I was constantly scolded for smiling. The

phrase “What's so funny?” was perpetually hurled in my direction. The school

principal once went as far as to say, looking straight at me, “Some people have

ceased to look human because things are always funny to them.” Similar

scenarios pursued me at the university and elsewhere throughout my life in

Soviet Russia.

Once, back in high school, things took quite a nasty turn. I

got on a tram with a group of my friends, and of course, I was smiling. The

tram conductor became very upset. She probably assumed that if I was smiling, I

was not intending to buy a ticket. Although I always bought a ticket on trams.

As soon as I ascended a couple of stairs, she hit me on the head with a broom.

In those days, tram doors were always open, and the blow caused my school cap

to fall off my head and roll down the stairs, out the door, and away on the

pavement.

At the next stop, I got out of the tram and wandered back to

look for my cap. That’s when I saw a policeman walking

toward me with my cap in hand. I told the policeman what happened to me on

the tram. And he replied that for my hooligan behavior, he would take me to

school and ask the staff to punish me. He really did bring me to school. As it

turned out, only teachers who did not tolerate smiles were around that day, and

they were very pleased by this turn of events. They warned me that I would soon

sink so low, it would be necessary to send me to a colony for juvenile

delinquents.

Of course, the fact that a smile rarely left my lips was not

all that serious a crime against the society in which I lived at the time.

What’s more, perhaps most importantly, it was not a deliberate act on my part.

It’s just that my face seemed somehow especially adapted to smile.

In short, I was not a nonconformist in the true sense of the

word, although I definitely possessed some nonconformist traits. So, looking

back, I would say I was about one-third-nonconformist.

* * *

In December of ’62, a major disaster befell Moscow avant-garde

artists. Their exhibition at one of the main Moscow venues, the Manege, fell

through. The whole thing was connected to the name of Ely Bielutin. He was the

head of the studio that united a large group of Moscow artists whose work went

against the official narrative supported by the communist regime. Ironically,

Bielutin’s studio was located on a street, the name of which, translated from

Russian, was the Big Street of Communism.

At the end of November ’62, Ely Bielutin’s studio organized an

exhibition, which received an enormously favorable response and was known as

the Taganskaya Exhibition. At that time, the Manege was hosting an exhibition

dedicated to the 30th anniversary of the Moscow Branch of the Union

of Artists (MOSCH). And Soviet officials ordered Bielutin to fill the halls of

the Manege with a display of avant-garde paintings.

When the main Soviet Party boss of that time – the Corn Man –

came to see this display, he was extremely annoyed by what he observed. He

shouted at the artists and threatened to deport them from the country. “The

Soviet people don’t need any of this!” was the mildest phrase he directed at

Bielutin. In the end, he gave instructions to ban avant-garde art in all its

manifestations.

What then appeared to be a major disaster, ultimately turned

out to be a great success, but nobody realized this at the time. And all

avant-garde artists struggled during this difficult period. But despite all the

problems, they decided not to give up. Instead, they began to exhibit paintings

in their own homes. They invited everybody to come to their apartments on

weekends while still dreaming of organizing broader and more open exhibitions.

Soon after the Manege exhibition in December ’62, Ekaterina

Pomanskaya, the mother of my university friend Lesha Pomansky, invited my

friends and me to a party at Bielutin’s residence. Pomanskaya was a member of

the MOSCH, although in some sense, she opposed the organization, and for this

reason, always suffered. She knew all of the Moscow avant-garde. She also knew

Bielutin well. That’s how we ended up at his party. It was, if I am not

mistaken, somewhere near Mayakovsky Square.

The party was a lot of fun. There were, of course, many

eyewitness stories told about how the Soviet corn-leader bellowed in the Manege

Gallery. It was at this party that I first heard the word “faggot,” pronounced

the same way the Corn Man did when referring to avant-garde artists. It was

also here that I first heard many jokes that I was to hear again countless

times. One such joke went “All the

members of the MOSCH don't measure up to the single member of Bosch.”

Shortly before that, an art book by Hieronymus Bosch came

into our possession, and we first “discovered” him for ourselves, becoming huge

admirers of his artworks. So I found this joke very funny and right on

target. Even now, when I recall it, I tend to smile.

Bielutin himself talked a lot about what happened at the Manege

Gallery. One story he shared was about Lesha Pomansky’s mother. At some point,

as the Corn Man was becoming increasingly furious, Dmitry Polyansky, a big shot

in Soviet governance, poured oil onto the Corn Man’s flaming temper. Polyansky

said his daughter had recently been presented with a picture of Ekaterina

Pomanskaya called “Lemons.” But actually, he said, what was depicted was not

lemons but just some sort of turds. Naturally, Polyansky’s remark had a

powerful impact on Pomanskaya and her reputation. She later had big problems

with the management of the MOSCH.

Bielutin also mentioned that when the Corn Man’s fury at the

Manege peaked, he began hurling insults starting with all the indecent letters

of the alphabet at everyone and their mother. At that moment, someone from his

entourage noted that there were ladies among those present. To which the Corn

Man replied that the ladies can also take a hike to places starting with those

same letters of the alphabet.

No one felt dejected at Bielutin’s party. Everyone was in great

spirits due to the pleasant company and the great ambience. Then, towards the

end of the gathering, Bielutin raised a clenched fist and shouted, “We’ll stage

them a Benz one day!”

For whom Bielutin was intending to stage a “Benz” was more or

less clear. The unclear part was what the word “Benz” actually meant.

Personally, I had never encountered it in such a context. But probably because

it sounded like a certain obscene Russian word, I guessed that it could not

mean anything good for the “them.” I doubt anyone was in the know at the time

as to what exactly that “Benz” entailed. I am not sure even Bielutin himself

knew. The Soviet authorities, however, had a much clearer understanding of what

kind of “Benzes” they would be doling out and to whom, and they inflicted them

quite generously.

It turned out, however, that Bielutin was right. The Soviet

avant-garde did stage everyone a “Benz,” one that proved more intense and

impactful than Bielutin or anyone else at that time ever could have dreamed.

Artworks created by the leaders of the Soviet avant-garde have now reached

museums all over the world, and the prices they command are astronomical.

* * *

In the mid-summer of ’66, my friends and I spent a few weeks in

Ukraine, in Crimea. We lived in Gurzuf, in the State House

of Artists.

Such houses were part of the grand plan of the Soviet authorities.

The first people to be targeted by them were writers. Because literature was

technically the simplest and easiest way to maintain and develop Soviet

ideology. Later, the writers were joined by members of other layers of society

– those who were in the public eye the most. This included cinematographers,

journalists, composers. And it also included artists. As a reward for obedience

and as an advance for future services to the Soviets, they were pampered in

various ways. They received special medical care, were allotted special feedings,

and had apartments and summer houses – dachas – built for them. However, even

the upper echelons of all these writers, composers, and artists overall lived

in poverty (in the normal sense of the word). Nonetheless, they did not at all

perceive this, since compared to the rest of the population, they were

undoubtedly in a position of privilege. And clearly, it was assumed that they

all understood perfectly that they could lose these privileges one day if they

were not sufficiently obedient.

The apartments and dachas built for them were concentrated in

specific locales. That way, monitoring them was considerably easier. Soviet

authorities built apartment complexes in Moscow for writers and composers. They

also constructed an artists’ village in the Upper Maslovka district of Moscow.

In addition to all that and for the same purpose, recreational

hotels were also built for these folks. They could live there for long periods

for free (or almost free) and were supposed to carry out their creative work

there, although the latter was not at all necessary. And that is what the State

House of Artists in Gurzuf was.

It was Lesha Pomansky’s stepfather, Grisha Zeitlin, who

arranged for us to live in this house. He too was an artist and a member of MOSCH.

But unlike Ekaterina Pomanskaya, he was an “obedient” member and therefore

successful. At the time, there happened to be available vouchers that the

artists had not wished to book and which were therefore going to go to waste.

So Grisha took advantage of this. That’s how we ended

up there.

I saw Grisha in passing only once or twice. I met Lesha’s

mother more frequently. She was a wonderful artist and an extraordinary woman.

I am obliged to Lesha and his mother for my entire art

education. Lesha, apparently, never created any artwork himself, but I received

a great number of technical tips from him. I learned about different painting

techniques. I found out where to get canvas, how it should be primed, and how

it needed to be mounted on a stretcher. I learned how to build the stretcher

and strengthen it with cross braces to prevent warping. Lesha also pointed out

that paints should not be mixed without paying attention to their components. Otherwise,

they may fade.

I learned many other useful things from Lesha as well. In

particular, he told me there were two extremely different groups of Moscow

artists. His mother belonged to one, while his stepfather belonged to the

other. On completing their daily projects, members of one group cleaned their

brushes with newspaper. By contrast, members of the other group cleaned their

brushes with soap and hot water.

I internalized all the very best offered by the Moscow school

of fine arts. I cleaned my brushes with newspaper and then washed them with

soap and hot water. Half a century down the line, I have improved upon this

technology and replaced the newspaper with the paper towel.

The roof of the House of Artists was under a canopy, and in the

middle of the day, the artists settled there with their easels. When I arrived there

for the first time, I wanted to join them. But the only thing I had brought to

Crimea other than clothing was snorkeling equipment. That was a problem.

Fortunately, there was a small art shop at the House of Artists. It held the

solution to my problem. I bought primed and unprimed cardboard, paints, paint

thinner, and even Chinese kolinsky brushes.

These brushes are made of hair obtained from the tail of the

Siberian weasel, or kolonok. Their quality is much higher than that of other

brushes made of natural or artificial hair. Now, such brushes are extremely

expensive. But at the House of Artists art shop, their

price, naturally, was quite low. Sadly, that was the only time in my entire

life in Soviet Russia that I was lucky enough to buy them.

So, I too settled on the roof, near the artists, who painted en

plein air. Really, it was peinture sur le motif. They painted what

their eyes actually saw. Their paintings depicted the sea, cliffs, and boats. In

short, these were real artists. There was never even a trace of

avant-gardists in that house.

I built an improvised easel and also began to paint en plein

air. Well, naturally, the way my eyes saw the objects. My paintings were

largely abstract. At any rate, they contained nothing even remotely resembling

the sea or cliffs.

I built an improvised easel and also began to paint en plein

air. Well, naturally, the way my eyes saw the objects. My paintings were

largely abstract. At any rate, they contained nothing even remotely resembling

the sea or cliffs.

From time to time, when I knew I was being observed by one

of the artists, I would have a bit of fun: I would look at the sea, then at my painting,

then back at the sea again, and then touch up the canvas with my brush. That

shocked my artists to no end.

I returned to Moscow with all the trophies I had acquired at

the art shop and continued to work on my painting. I also tried getting to know

more artists of the Moscow underground. On weekends, on the advice of Lesha’s

mother, I visited Moscow artists’ apartments. From then on, it was all pretty

straightforward. Once I learned about a painting exhibition at one apartment, I

always found an ad there with the address of the next apartment to exhibit work.

That’s how I ended up attending possibly every single

apartment exhibition in Moscow. Naturally, Oskar Rabin’s one was among

them. Lesha’s mother was the one who took us to visit him in Lianozovo. And it

was there that I saw all his paintings for the first time. His Madonna against

the background of local barracks really appealed to me. I recall Lesha’s mother

noticing this, and we stood before that painting together for some time. We ended

up spending about half a day at Rabin’s.

As I continued to meet Moscow artists, I closely tracked

how Ekaterina Pomanskaya worked. At some point, I learned that she produced

linocuts. Quite possibly, Picasso’s linocuts had influenced her. “Lemons,” the

work criticized by Soviet authorities at the Manege Gallery, was actually a

linocut as well. I really liked Pomanskaya’s artworks. So when Lesha taught me

how to make a linocut, I decided to try the technique myself. I got linoleum

and wood carving tools – chisels and gouges. Then I made a very simple printing

press. Other necessary tools included a special paint for the press, which

Lesha found somewhere for me, and a rubber roller, which all of us normally

used for glossing photos. Lesha, however, warned me that his mother did not

trust that roller much and instead used a plain tablespoon when working on the

details of her linocuts.

As I continued to meet Moscow artists, I closely tracked

how Ekaterina Pomanskaya worked. At some point, I learned that she produced

linocuts. Quite possibly, Picasso’s linocuts had influenced her. “Lemons,” the

work criticized by Soviet authorities at the Manege Gallery, was actually a

linocut as well. I really liked Pomanskaya’s artworks. So when Lesha taught me

how to make a linocut, I decided to try the technique myself. I got linoleum

and wood carving tools – chisels and gouges. Then I made a very simple printing

press. Other necessary tools included a special paint for the press, which

Lesha found somewhere for me, and a rubber roller, which all of us normally

used for glossing photos. Lesha, however, warned me that his mother did not

trust that roller much and instead used a plain tablespoon when working on the

details of her linocuts.

So, I made a couple of linocuts. Then Lesha guided me in making

a couple of monotypes, again using techniques he had learned from his mother.

She used regular glass instead of a copper etching plate as the matrix for her

monotype images. So did I. Unfortunately, neither my linocuts nor my monotypes

survived. All of them were lost somewhere during my pilgrimage from Russia to

America.

Somewhere in the late nineties, Lesha Pomansky gave me two of

his mother’s original linocuts as a present. To this

day, I have them in my Millburn home in New Jersey. One of them, “The

Pomegranate,” was always a particular favorite of mine.

* * *

Four years after the Manege exhibition, one of the milestone

exhibitions of paintings by the Moscow nonconformists finally took place.

Twelve artists took part in this event. Eight of them belonged to the so-called

Lianozovo group: Evgeny Kropivnitsky (the guru of the group), Oscar Rabin,

Vladimir Nemukhin, Lidiya Masterkova, Nikolai Vechtomov, Olga Potapova (wife of

Evgeny Kropivnitsky), Lev Kropivnitsky (son of Evgeny Kropivnitsky and Olga

Potapova), and Valentina Kropivnitskaya (Oscar Rabin’s wife, and daughter of

Evgeny Kropivnitsky and Olga Potapova). The other four participants in this

event, who did not belong to the Lianozovo group, were Dmitri Plavinsky,

Anatoly Zverev, Eduard Steinberg, and Valentin Vorobiev.

The exhibition was hosted by the “Friendship” club, which

belonged to an organization where I worked at the time. The organization was

called P.O.Box 702. This unusual name meant that the institution was

considered secret. At the time, secret organizations were common throughout the

country, although I seriously doubt any actual technological secrets could be

found there. What the Soviets were trying to keep secret were things like the

exact nature of the work being carried out at a specific organization, how low

the quality of its overall activity was, or which technological secrets were

being “borrowed” from the West. Our P.O.Box

met the criteria for all three such types of secrets.

On the part of our P.O.Box,

young people and technical personnel from the club worked together to arrange

the exhibition. On the artists’ end, the organizer was Oscar Rabin. Liaising

between the P.O.Box and the artists was

Alexander Glezer. He was well-acquainted with those of our young people

slightly older than me. I no longer remember how Glezer got to know them, but they

knew each other very well. It is possible that at

some point, Glezer worked at our P.O.Box

or at a related institution. And he was actually the one who organized the “Exhibition

of Twelve.”

Glezer came across an old acquaintance of his, who knew

absolutely nothing about avant-gardists. They came to me. In our organization,

I was the indisputable authority on fine arts. When I learned they were talking

about Rabin and his friends, I gave my immediate go ahead for the exhibit. The

only thing I did not mention was how risky it was to get involved in such

affairs. And they were completely naïve in that respect. So what happened next

seemed like thunder out of clear skies.

The exhibition opened on Sunday, January 22, 1967. It was assumed

that it would last for some time. I, however, was not at all certain about

that. I suspected it might be shut down the day it opened. So I decided to go

there on that Sunday. The head of our local branch of the Communist Party,

Zlata Preobrazhenskaya, announced that she was planning to check whether

everything was in order prior to the opening of the exhibition, and then would

have to leave. And I volunteered to represent our P.O.Box at the opening and turned out

to be alone on that count.

Everyone else from our P.O.Box who wanted to attend

the exhibition had decided that it wasn’t worth wasting half of their weekend

on it. They assumed it would be better to peruse the exhibition halls without

rushing in the days that followed, during working hours.

On opening day, I was one hundred percent certain the

exhibition would be shut down immediately and accompanied by a considerable

scandal. My certainty stemmed from seeing a multitude of cars with quaint

foreign outlines conveniently parked around our super-secret organization. I

expected the KGB to take harsh, decisive measures.

My predictions proved correct. The exhibition lasted only a

couple of hours before being shut down by the KGB. I had left the building

shortly before the fateful moment and learned about it only the following

morning, on Monday. I went to the “Friendship” club before the start of my work

shift and encountered completely empty halls, with ends of cut rope drooping desolately

along the walls.

Our P. O. Box then ended up under heavy fire from the

KGB and Moscow branches of the Communist Party. For some reason, the KGB forgot

about our youth. However, the one to come under fire was our Zlata. In his book

“Contemporary Russian Art,” Alexander Glezer wrote in detail about all aspects

of the exhibition, including his negative impression of Zlata. If his words

about her were painted, they would all be in tones of gray. I would hesitate to

doubt the veracity of the exhibition’s twists and turns as portrayed by Glazer.

His descriptions are very plausible. But in my opinion, Zlata deserves lighter

tones.

Why do I think so? Well, for one thing, right after the closing

of the Exhibition of Twelve, I expected at least some criticism from Zlata

regarding my role in the exhibition, but none came. On the contrary, it seemed

to me that during our chance encounters, Zlata began to greet me with obvious

affection. Once, we had a brief conversation on a subject of no particular

relevance here. At some point, in disagreeing with her, I pushed my

counter-argument a bit further than she liked. When she thought I was about to

say something inadmissible (in her understanding),

she looked me in the eye and with a faint smile said “Stop! I know you. It

seems to me you are bound to say something inappropriate. I don’t wish to hear

it.” That was the end of our conversation.

For anyone unfamiliar with those times, I have to say that given Zlata’s position, it would have been normal, or rather mandatory, for her to hear me out and convey the

content of our conversation to the authorities – straight to the KGB.

Although both Glezer and I were at the Exhibition of Twelve, we

did not chance to meet. In fact, I never met him, even after he moved his

Museum of Modern Russian Art from France to New Jersey. I got to meet those who

headed the Jersey City museum only after Glezer had left it.

After the Exhibition of Twelve was dismantled, the Moscow

nonconformist artists became discouraged but did not give up. They worked

underground, continuing to paint and even sell their works from time to time.

Many of them even managed to make a living through their art. Even though they

sold their paintings for next to nothing.

In those days, even paintings by recognized Russian masters could

not be sold for a lot. I am referring to paintings from private collections.

Everyone lived like a pauper. No one in the country had any money to spare. And

those rare individuals who did have a bit of money, had to hide the fact. For

these reasons, the art market was not very liquid.

Once, I was involuntarily drawn into selling such paintings.

One of my friends, Kira, had unexpectedly received a sizable inheritance when

her uncle died. He was a good doctor, and what’s more, he had access to the

limited State medical resources. Such doctors were quite wealthy at that time.

Their activities were, to a large extent, illegal, but they were privately

protected by certain high-ranking officials. This uncle left Kira his entire

fortune: money, jewelry, and paintings by Russian masters.

At the time, I lived in Neopalimovsky Lane. Kira lived in an

old building one street over. She told me the walls of her apartment had such

big holes that she could see everything outside. To keep diamonds, sapphires,

and paintings in such a home would be insane, so

she brought all her treasures to our apartment. I hung all her paintings on the

walls. There were works by Repin, Kustodiev, Nickolas Roerich, Manevich,

Petrov-Vodkin, and Korovin.

At the time, Kira was living on her own, quietly and

discreetly. Then suddenly, everything changed dramatically. Men of means became

attracted to her. Our home started being frequented by respectable people. They

engaged in intellectual conversations and made it clear that they were not

merely respectable people but very respectable people. At times they would

bring quite outlandish items. I recall when one of the respectables brought

half a bottle of Calvados. And he went on at length, explaining what it was. He

obviously did not expect to find proper glasses at our place, so he brought

along his own. And then went on explaining the correct temperature and proper

glasses for drinking Calvados in order to properly preserve its aroma, and

while at it, pricing the diamonds and the paintings.

It was not long before a small work by Repin was sold for 500

rubles. A large work of Kustodiev’s titled “Flowers,” was eventually sold for

800 rubles. Kira was told not to sell the Roerich for less than 5,000, but that

price attracted no buyers. The best offer for the Roerich was 2,000, which was

why that painting remained at our home longer than the others.

Those were the post-reform days. I was earning a hundred rubles

a month. The salary of a PhD was anywhere between 300 and 400 rubles. Butter,

cheese, and sausages cost about 3 rubles per kilo. A bottle of vodka was sold for

2 rubles and 87 kopecks.

Kira was introduced to people from galleries. She was invited

to the Tretyakov Gallery on Krymsky Val, which was right near our apartment, to

see their “foundation,” or what was hidden behind the walls of their depository

and unavailable to a wide audience. Kira took me with her. There were several

big rooms that smelled of dust and contained nothing but shelves with small

gaps between them. The shelves housed paintings by those Russian artists who,

in the opinion of the country’s leaders, “were not needed by the Soviet

people.” The paintings were stacked tightly and haphazardly. Some were in

frames, others just on canvas stretchers. The smell of dust permeated

everything. It was possible to look at a painting only by picking it up from a

rack and leaning it on the floor against a nearby wall.

At some point, I began to pull a huge painting from one of the top

shelves. Its diameter alone was about one and a half meters. So it was

difficult for me to drag it by the frame without touching the canvas with my

hands. And when it started to fall on me, I was forced to hold it by the

canvas. I set the painting on the floor and leaned it against the wall. The

artist and his wife were flying above their native Vitebsk.

I had been fortunate enough to leaf through an album of Marc

Chagall’s work shortly before my trip to the Tretyakov Gallery. I guessed it

was possible for some of his works to be in Russia. But it was hard for me to

believe that his “Over the Town” painting was just a 10-minute walk from where

I happened to live then.

* * *

I had always been surprised by the extreme inconsistency in all

the banditry of the Soviet authorities. (Now I understand that I should not

have been surprised.) They considered the work of the Russian avant-gardists to

be garbage. But for those who wanted to export this “garbage” and take these

paintings abroad, things became difficult. Avant-garde

paintings were starting to be considered the equals of other artworks. And obtaining a permit to export the paintings turned into

a very complicated process. Most of the time, it was necessary for the

owner of the “garbage” to proffer a bribe. He had to find the right people, so

the bribe offered at one end of the transaction would be safely accepted at the

other end. As a rule, the offeror of a bribe extended deep (and sincere!)

gratitude toward the offeree, who felt profound satisfaction due to both the

financial output of the deal and the feeling that a good deed had been done.

In 1989, a colleague and close friend of those years, Gena

Ioffe, was leaving Russia for what was presumed to be forever. He was married

to Anna Plavinskaya, the daughter of Dmitri Plavinsky. Gena and Anna were

bringing with them works by Russian artists. Needless to say, they had obtained

all the necessary permits for their export. Among these works,

Gena had a

present I had given him – a collage I had created, entitled “Baba with

Earrings.” I accompanied Gena to the airport and watched as the customs officer

checked all the artworks and export documents. Everything was fine until he got

to my piece. The customs officer asked to see the relevant export permit. Gena

replied that a permit for this work was not required, because it was created by

his friend. And he nodded in my direction. The customs officer looked me up and

down and eventually concurred that indeed my work did not require a permit.

In 1989, a colleague and close friend of those years, Gena

Ioffe, was leaving Russia for what was presumed to be forever. He was married

to Anna Plavinskaya, the daughter of Dmitri Plavinsky. Gena and Anna were

bringing with them works by Russian artists. Needless to say, they had obtained

all the necessary permits for their export. Among these works,

Gena had a

present I had given him – a collage I had created, entitled “Baba with

Earrings.” I accompanied Gena to the airport and watched as the customs officer

checked all the artworks and export documents. Everything was fine until he got

to my piece. The customs officer asked to see the relevant export permit. Gena

replied that a permit for this work was not required, because it was created by

his friend. And he nodded in my direction. The customs officer looked me up and

down and eventually concurred that indeed my work did not require a permit.

“Baba” was one of my last creations before departing Russia. It

was my attempt to create something using a technique other than painting.

* * *

I don’t know why, but the entire time I lived in Russia, I

wanted to make something out of clay. I just didn’t know how to go about it. And

then one day I was returning home from somewhere in the rain. I was splashing

through puddles, my shoes sinking in dirty muck. And in all that muck I noticed

a few white patches. I marked the place, and when the rain had stopped and

everything had dried out, I returned and managed to dig up something that

looked like white clay. Of course, this clay was very muddy, but I knew how to

deal with that. I started tapping my lump of clay against the concrete steps of

the porch – a trick I’d learned from the boys in

the building where I lived the first 17 years of my life. The dirt gradually

began disappearing, and soon I had a decent-size piece of fairly clean clay in

my hand.

Out of this clay, I made a plate and left it to dry for a

couple of weeks. Then I put it in a regular gas oven to bake. Fortunately, my

plate did not crack, although it would have remained very fragile. While I do

not believe any structural changes had occurred during this firing, the plate

was somewhat better than just greenware. Quite pleased, I “glazed” the plate

with oil paint. It turned out pretty crappy.

Later I decided to approach the problem from the other side.

I took a regular ceramic saucer and painted an image on it. This time, I used

oil paint mixed with epoxy glue. I liked the outcome of these efforts somewhat

more than the previous one. The photo from the end of 1970 shows me examining that

saucer. I don’t look particularly respectable there – I am, after all, merely

28 years old. But in those days, I had three children. And I had already

managed to achieve a few successes, which pleased me immensely and seemed very important

at the time, in 1970.

Later I decided to approach the problem from the other side.

I took a regular ceramic saucer and painted an image on it. This time, I used

oil paint mixed with epoxy glue. I liked the outcome of these efforts somewhat

more than the previous one. The photo from the end of 1970 shows me examining that

saucer. I don’t look particularly respectable there – I am, after all, merely

28 years old. But in those days, I had three children. And I had already

managed to achieve a few successes, which pleased me immensely and seemed very important

at the time, in 1970.

Ten years later, I made my third, more serious, attempt to work

with ceramics. By this time in my life, my friends and I had established a

beekeeping partnership. None of us had any experience in this matter. Nor did

we have any funds necessary to launch our enterprise. Not to mention that we

came up with this idea in a country where private entrepreneurship was

considered the greatest sin. Nonetheless, this venture, guaranteed to be

fraught with risk, was something we committed to pursuing.

When not busy with our bees, we intended to do something “for

the soul.” One such venture was going to be ceramics. We had a plan. We were

going to buy a house in a village, bring our bees there, and then, in our spare

time, dig a big pit in our yard and line its walls, floor, and ceiling with bricks.

That was going to be our kiln for firing ceramics. Then we were going to find some

open-pit mine from which to dig up clay. And out of this clay

we intended to craft and fire Japanese ceramics.

My friends and I did buy a house in a village (in the Voronezh

Region). Our village was called Bogana. There, in the backyard of our house, we

intended to launch our ceramics project. However, its fine points were not

quite clear to me nor, I would imagine, to the others. Why and how would we manage

to fire Japanese ceramics in a small village in the middle of nowhere, using a

simple pit lined with ordinary Soviet bricks and heated with Russian birch

firewood? How were we going to glaze our Japanese ceramics? In what open-pit

mine were we going to dig up the glaze components? I do not think we even knew

what glaze was, because the word, to my recollection, never even crossed our

lips.

One of the problems with the implementation of our project was

that our house in Bogana was our base. We kept the bees there only during the

off seasons: in the fall, winter, and early spring, during which time we went

to the base only rarely. In the middle of spring, we moved our bees more than

100 kilometers and stayed there until the end of the largest honey flow. During

that period, none of us ever went to Bogana.

Another problem with our ceramics project was that there were

too many people involved. Each had his own ideas about what things needed to be

done and how. As a result, the project proceeded slowly and irrationally.

Digging the big pit in the backyard of our house was not

difficult, and that part of the plan was accomplished by the end of our second

year. Soon after, we bought bricks, but we didn’t do anything with them until a

couple of years later. By that time, it was clear we would never finish our

ceramics project. However, nobody was upset, because from the very beginning,

it had a low priority in the scheme of things. Some time later, we did finally line

the pit with the bricks and put our “kiln” to good use. We used it as the

foundation for a good shed for overwintering our bees. We ended up producing

almost 20 tons of honey per season. So no one had any regrets about the

unsuccessful attempt at Japanese ceramics.

So I never got the chance to work with clay in Russia, although

I thought about it for as long as I can remember. But in Russia, it was

difficult to make my dreams come true. And my next attempt to develop ceramics skills

was made significantly later, after my departure from that country.

* * *

I arrived in America in the fall of ’91. At first, I couldn’t

think of anything other than finding at least some kind of work. It turned out

not to be all that easy. I was trying to find a job in the field of

mathematical statistics, in which I was quite fluent and had already published

several monographs. My area of specialization was very narrow. Nonetheless, I

found a company where a large team of mathematicians and programmers was working

on precisely what I considered myself to be the top specialist. They invited me

to an interview and started describing what type of work they did. At the time,

I didn’t have a very clear idea of how to behave in that type of a situation. And

rather carelessly, I told my interviewers that they were on the wrong track,

which would fail to lead them to their goal. And that what they had set out to

accomplish, I could achieve singlehandedly within a few months. They thanked me

for an interesting discussion, said goodbye, and promised to call. But they

never called. And I never did find out why. Either I had really scared them or

they simply thought I was insane.

I kept looking for a job. And although I kept telling

myself that I should not distract myself with anything else, I managed to

create several collages during that period. Using this technique was obviously

not all that costly (in terms of the time spent). I also made something akin to

a self-portrait. I simply placed my head on the scanner and got a printout. Then

I used the same scanner to make several enlarged and reduced versions. What I

got in the end was a composition which I titled “The Infinitely Large and the Infinitely

Small.”

Not long after, I learned from a local newspaper that the

National Institute of Standards and Technology was offering a research program

(ASA/NSF/NIST Senior Research Fellow Program) in 1992–1993. One of their topics

was again in that same area in which I considered myself to be the most

proficient in the world. The contract was for less than a year. But the salary

they were offering seemed to me to be completely astronomical.

I submitted my proposal. Then sent additional materials at the

request of the institute. At some point I was asked what kind of assistants I

would need and in what numbers. To which I obviously replied that I didn’t need

any assistants at all and that I would complete the work by myself. Although

this time I had the common sense to keep my mouth shut about being able to

finish everything in a couple of months. After some time, I was notified that

my proposal had been pre-approved and that I had to go through a final

telephone interview with a representative of the institute.

The interviewer asked me some questions and I answered.

Naturally, I had no problems with the substance of those questions. To be more

precise, I shouldn’t have had any problems with those questions. But I had only

been in the country for a few months and did not have a good grasp of American

English (especially over the phone). At one point, my interviewer asked whether

I was familiar with the work of Addelman. Of course, I was well-versed in all

his work, and I even expanded one of his results into a more complex case. But

the pronunciation of the surname Addelman by my interviewer did not sound to me

quite as I then assumed it should have sounded, and the stress on the first

syllable threw me off completely. And I replied, “I don’t know him!” Although

this had a rather biblical ring to it, apparently it turned out to be the final

straw in our already tense (through my fault, of course) conversation. As a

result, the National Institute of Standards and Technology rejected my proposal.

I think it was a big mistake on the part of the National Institute

of Standards. But ultimately, it ended up being a great stroke of luck for me. Because

at that moment I had finally made the right decision. I decided to forget

everything I had done in Russia. And I started reading book after book on

financial mathematics. Soon, and with the help of Gena Ioffe (who had dragged

my “Baba” collage through Soviet customs three years earlier), I got a project

at a small firm developing software for Wall Street companies. The project was

linked to financial mathematics. And a couple of months after I successfully

completed it, I was offered a permanent position at this firm.

By '94, I was already working at Chase, the largest bank in

America at the time. With my financial situation secure, by 1996, I realized I could

think about more than just making money. At the time, I

was living in Millburn (New Jersey). I decided to take a ceramics class offered

at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey in the neighboring town of Summit. I

liked it so much that I took more classes over the next several years, studying

and working under the guidance of the only ceramics teacher I have ever had,

Carole Chesek.

By '94, I was already working at Chase, the largest bank in

America at the time. With my financial situation secure, by 1996, I realized I could

think about more than just making money. At the time, I

was living in Millburn (New Jersey). I decided to take a ceramics class offered

at the Visual Arts Center of New Jersey in the neighboring town of Summit. I

liked it so much that I took more classes over the next several years, studying

and working under the guidance of the only ceramics teacher I have ever had,

Carole Chesek.

I found learning at the Visual Arts Center wonderful in every

respect. The only problem was that I made my ceramic plates too fast. I sent

them for firing one after another, and the people responsible for the firing

began to grumble a bit. They complained that my work constituted a significant

portion of the items from the entire ceramics class and began to introduce various

restrictions that they’d never had before. Carole took my side in a small

confrontation with the kiln people, and the issue seemed to be resolved.

Then something difficult to explain took place. One day, after

a firing, none of my plates were returned to me from the kiln. I complained

about it to Carole, and she suggested that perhaps they had been assigned to

the next kiln loading. She advised me to wait several days. I followed her suggestion,

but my plates never did turn up. Carole said she could not imagine how such a

thing might happen. And that although anyone could enter the building, never in

the history of the studio had ceramic works been “borrowed.” And if that’s what

had happened to my art, she said I should be proud.

At some point, when Carole realized the new firing restrictions

were bothering me more and more, she advised me to set up a ceramics workshop

in my own house. Recalling my Bogana experience, I was not very enthusiastic

about the suggestion at first. But then I realized I didn’t need to dig a big

pit in my Millburn backyard or line its walls, floor, and ceiling with bricks.

Nor did I need access to an open-pit mine to dig up clay. I could buy

everything in a ceramics shop that was a 20-minute drive from my home.

Furthermore, I hoped that if I did everything myself, there

would be no confusion or irrationality involved. I entertained this hope for

the following reason. Back in Russia, I had been fortunate to read Fred Brooks’

book on software engineering and project management. The central idea of the

book was that “adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” This

idea is known as Brooks’ law. As I reflected upon that maxim, along with my

experiences in the beekeeping partnership and in American financial industry, I

formulated a new law: When working on a project, if you can do everything

yourself, it is better to work alone and without any help, from start to finish.

Although this approach was not particularly popular in the

large financial companies where I got to work, I completed my projects there

almost exclusively by myself. And in all my long years of employment, I never

had anyone work under my direct supervision. I would not be surprised if, given

the positions I held there, it turned out that I was the only such person in the

financial industry.

When someone is helping you with a project, you can certainly

distribute all the work and thereby try to save time. Unfortunately, however,

some team members may work many times more slowly than others. And most

importantly, the team spends enormous amounts of time and resources on endless

discussions about the choice of strategies, on keeping all participants up to

date, on coordinating tasks, and simply on maintaining their livelihood.

So, when I realized I could do everything related to my

ceramics projects myself, I decided to do just that. Even though, I knew that

no self-respecting artist would act the same. Miro did not cast his bronze

figures himself. His sculptures were cast in bronze at foundries in Barcelona

and Paris. Picasso got important technical help from professional ceramists

working at the Madoura Pottery workshop in Vallauris in the south of France.

A good friend of mine (I will call him Jake here) once

described to me the creative process of working with one particular

internationally-renowned sculptor. The sculptor supplied Jake with only very

general ideas about how the sculpture should look. Then Jake would start the

work by creating an initial model in plasticine. The famous sculptor and his

wife would then visit Jake, whereupon Jake received more instructions, this

time on how and what to change. He might be told, “Here, the hand should be raised

a little,” or “The girdle should be a little wider here.” The funny thing was

that the sculptor himself did not ask Jake to change anything. He was quite

happy with what Jake was doing. The tips and changes came from the sculptor’s

wife.

Once the plasticine figures were in finished form, they were

sent away for further standard processing to which neither the sculptor nor

Jake had any connection. The end result was nice bronze figures, which I later

saw in galleries – under the name of the famous sculptor, of course.

* * *

So, I decided that I would do

everything myself. Naturally, the setting up of a ceramics studio in my house

in Millburn started with a kiln, which I acquired from someone Carole had

recommended. I allocated about 500 square feet in the basement of the house

and about 300 square feet in the garage for my workspace. Gradually, I filled

both with numerous open shelves and tables.

I fire my ceramics in the garage. It contains two kilns, all

the necessary kiln furniture, and other equipment and tools needed for firing.

My garage is not attached to the house, which would have been inconvenient if I

had wanted to keep my cars there. But for my purposes, a detached garage turned

out to be of great advantage. During firing, carbon monoxide emissions can

exceed threshold limits. This and other chemical emissions are not good for the

health, which is why firing areas should always have adequate ventilation. And

the fact that the garage is not attached to the house effectively removes the

ventilation problem. As for my cars, none of them ever made it into the garage.

Other than firing, I do all of my work in the basement, which

is primarily dedicated to my ceramics workshop. One room ended up serving as an

exhibition facility for much of my work. However, I cannot say I keep my best

work there. The best pieces are either scattered around the walls of the main

rooms of my houses or in the possession of those to whom I gifted my ceramics.

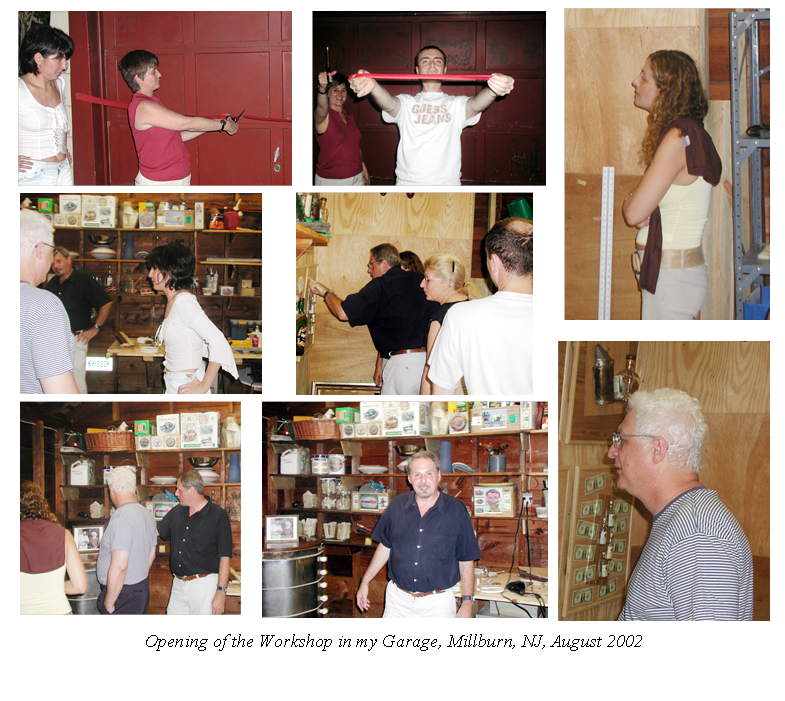

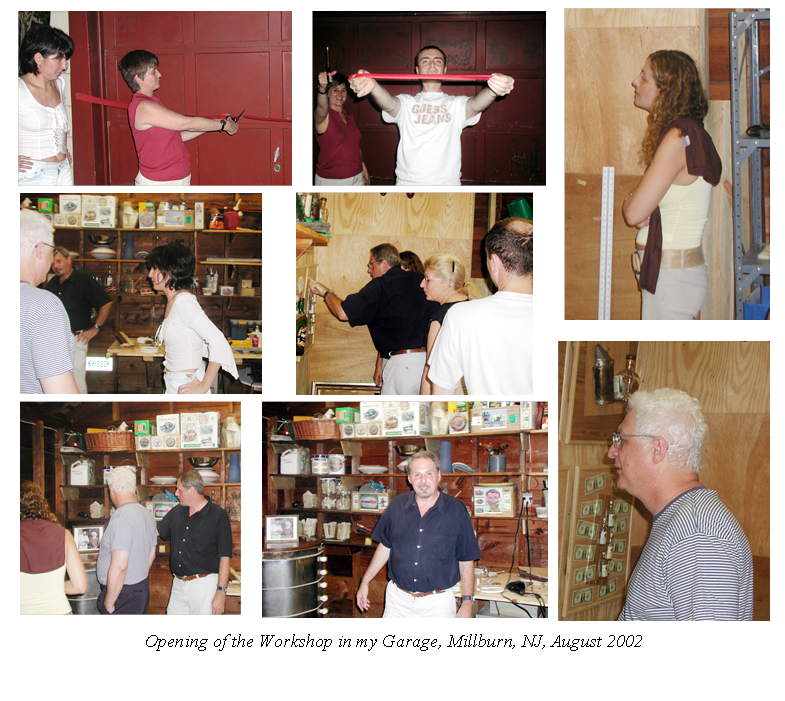

On Sunday, August

18, 2002, we gathered at my Millburn home for a barbecue to celebrate the

official opening of my garage workshop. The occasion was very festive and

included a ribbon-cutting ceremony. The mistress of the house, my wife Natasha,

cut the red ribbon. Then we took our time inspecting the garage exhibition, drinking

copious amounts of champagne, and eating a great deal of food. So the opening

of the workshop ended up being a great success.

* * *

I never intended to throw many pots. Nevertheless, I have a

pottery wheel, and I often use it in my work. There is, however, one additional

reason why keeping a pottery wheel is indispensable. The thing is, I often have

visitors who want to see my workshop. The first thing people ask about when

they go down to the basement is the pottery wheel. Actually, people

usually do not use those specific words because they do not know

them. Instead they start wrinkling their brow and gesturing with their hands

until I help them with the relevant ceramics terminology. It seems to me that

not having a pottery wheel in such situations would be tactically incorrect.

I never intended to throw many pots. Nevertheless, I have a

pottery wheel, and I often use it in my work. There is, however, one additional

reason why keeping a pottery wheel is indispensable. The thing is, I often have

visitors who want to see my workshop. The first thing people ask about when

they go down to the basement is the pottery wheel. Actually, people

usually do not use those specific words because they do not know

them. Instead they start wrinkling their brow and gesturing with their hands

until I help them with the relevant ceramics terminology. It seems to me that

not having a pottery wheel in such situations would be tactically incorrect.

I fire everything in electric kilns. These have no open

flame. For that reason, the atmosphere is very rich in oxygen. And it is

therefore not possible to get certain types of visual effects, which would be

easily obtainable when using kilns that run on liquid, solid, or gaseous fuels.

I found such effects quite appealing but realized that I would not be able to

find the extra time necessary for such experiments. The only thing I once

ventured to try was firing my ceramics in a raku kiln. Technically, this type

of firing is quite straighforward since the raku kiln is a low-temperature one.

It is used for rapid firing. Only it is necessary to take the piece out while

it is still red-hot and to transfer it from the kiln to some easily-flammable

combustible material. Upon going through all the steps and analyzing the

result, I realized that such a technique would not add anything positive to my

style. That is why ultimately, I ended up using an electric kiln.

So far, I have been fortunate and have never experienced a kiln

disaster or suffered other serious kiln problems. I have not even had any of my

greenware explode in the kiln. I have been spared such losses for several reasons.

First, I do not make thick-walled pieces. Second, I make sure there are no air

bubbles inside the clay. And third, I dry my greenware over a period of about

two to three weeks. The lengthy drying period results in greenware that is bone-dry

before it goes through its first firing.

So far, I have been fortunate and have never experienced a kiln

disaster or suffered other serious kiln problems. I have not even had any of my

greenware explode in the kiln. I have been spared such losses for several reasons.

First, I do not make thick-walled pieces. Second, I make sure there are no air

bubbles inside the clay. And third, I dry my greenware over a period of about

two to three weeks. The lengthy drying period results in greenware that is bone-dry

before it goes through its first firing.

I have never thought about an overnight warm up. I consider it

an unnecessary precaution. Instead, before the bisque firing, I keep the kiln temperature

low for a couple of hours with the lid slightly open. I intend to continue

employing this strategy until the first explosion in my kiln, which, I hope,

will never occur.

I fire all my ceramics twice. I bisque fire my items to cone

06, and most of the time, I glaze fire them to cone 6. Therefore, almost all of

my ceramics are stoneware.

I do not make my own clay. Instead, I buy it ready-made

in ceramics shops. First, I started using plastic clay, which has a smooth

throwing body. It is fit for many purposes, and ideal on a pottery wheel. The

only problem is that flat items (in my case, plates) made of plastic clay can

warp. At first, I did not pay much attention to warpage. But later, I began battling

the problem. For several years, I tried to solve it by myself. First, I tried

making my plates thinner. They continued warping. Then I tried making them

thicker, and then thicker still. None of these strategies led to success. Then

I complained about my problem at the Summit studio and was advised to craft

each plate from a single, whole piece of clay. It turns out that adding extra

pieces to clay generates heterogeneity, which causes warping. That obvious consideration

had not occurred to me on my own.

After that, I began to use only whole pieces of clay. I

experimented with them for a couple of years but realized that items made of

homogeneous clay were still warping. Then someone advised me to use clay with

grog. My plates stopped warping but began to crack frequently, especially those

of bigger sizes. When I complained to someone about that problem, I was advised

to use plastic clay. The problem-solving suggestions had come full circle.

However, I eventually solved the problem on my own, and my plates stopped

warping or cracking.

After that, I began to use only whole pieces of clay. I

experimented with them for a couple of years but realized that items made of

homogeneous clay were still warping. Then someone advised me to use clay with

grog. My plates stopped warping but began to crack frequently, especially those

of bigger sizes. When I complained to someone about that problem, I was advised

to use plastic clay. The problem-solving suggestions had come full circle.

However, I eventually solved the problem on my own, and my plates stopped

warping or cracking.

I make about half of my glazes myself, using raw

ingredients I buy in ceramics stores. The recipes I follow are based on ideas I

got in classes at the Summit studio. It would be inconvenient to go to the shop

each time I needed a particular glaze component. On the other hand, there is an

enormous number of potential ingredients. Therefore, I started keeping a set of

only the most useful chemicals at home. With that in mind, I only buy as many

chemicals as can fit into the basement cabinet. The “most useful chemicals” have

added up to around 70. These 70 compounds enable me to make approximately 50

different glazes.

In addition to homemade glazes, I use about an equal number of

commercial ones. Sometimes I add chemicals to the commercial glazes to change

them a little and adapt them to my needs.

In addition to homemade glazes, I use about an equal number of

commercial ones. Sometimes I add chemicals to the commercial glazes to change

them a little and adapt them to my needs.

When preparing homemade glazes or modifying commercial ones, I run

into one problem. From time to time, I discover that the ceramics stores don’t stock

a product I need for a specific recipe. Although

sometimes it turns out that a store does sell it but under an

alternative name. At other times, it

simply turns out that the product I need is no longer produced. Glazing

ingredients may be discontinued as a result of a fire at the mine where they

are procured, or because the extraction process becomes unprofitable due to the

depletion of necessary resources, or for a multitude of other reasons.

When glazing chemicals become unavailable, ceramics stores sell

substitutes. However, I am unable to distinguish between an alternative name

and a substitution. Furthermore, when it comes to substitutions, I am far from being

sufficiently educated to understand how small variations in chemicals will end

up influencing the resulting glaze and how undesirable outcomes can be avoided

or minimized.

For example, F4 Feldspar is considered to be the same as Sodium

Feldspar, Kona Feldspar, Kona F4, F4 Spar, NC-4 Feldspar, NC-4 Soda Feldspar,

and Minspar 200. Perhaps that is the case,

at least in the practical sense. But I know there are differences in almost

all eight of the components

that make up NC-4 Feldspar and F4 Feldspar. And although at one point, I had

both F4 Feldspar and NC-4 Feldspar, I was far from eager to start testing them.

I have never had time for such experiments. I simply switched from one to the

other. And when I realized I could not discern any significant differences

between them, stopped worrying about the whole thing.

I can say the same about such names as Zircopax, Zirconium

Silicate, Zircon, Zircopax Plus, Superpax, Zircosil, Excelopax, and Ultrox. At

some point, I stopped fretting and trying to distinguish between alternative

names and substitutions. Instead, I decided that they all suited me fine.

Once a person overcomes concerns with the problem of using

alternative products, glaze preparation becomes a fairly straightforward

operation. But making glazes does require very accurate scales, because even a

very small error in the weighing of the ingredients can lead to disappointing

results.

Once a person overcomes concerns with the problem of using

alternative products, glaze preparation becomes a fairly straightforward

operation. But making glazes does require very accurate scales, because even a

very small error in the weighing of the ingredients can lead to disappointing

results.

I often employ the slip-casting technique. Mostly, I use it to

create specific parts of my ceramic works. I usually make molds for

slip-casting myself. Creating molds is a time-consuming process, especially if

their design is complex. To produce such molds, one needs to possess a good

stereometric imagination.

Many who need molds for their work reject the idea of making

their own, mostly because they lack a stereometric imagination. I once heard

about a young man who had no stereometric imagination and who decided to order

customized molds. However, customized molds are very expensive. And the young

man decided to take on additional jobs to be able to afford such a luxury. He

began to teach mathematics at a college. One concept he needed to teach was

stereometry. However, that did not bother him at all. And he was probably right.

After all, teaching something is completely different from using that knowledge.

A friend of mine, Genrikh Granovsky, who was a

professional teacher and who happened to be very bright but perhaps excessively

self-critical, once told me, “I don’t know how to do anything in this life,

so there is nothing left for me but to teach others.”

My molds don’t look particularly elegant, but they fulfill

their functional purpose. One disadvantage of using handmade molds is that they

are often quite cumbersome. When they are filled with liquid clay, they become

very heavy and difficult to lift, turn, and hold in position for several

minutes when the clay needs to be poured out. For instance, my biggest plaster

mold weighs a fair amount on its own and holds three gallons of liquid clay. So

it is completely beyond my strength. For this reason, I was forced to devise a

hoist system in my basement for the excessively heavy molds. I screwed a hook

into the ceiling and attached a chain hoist to it. This allows me to lift,

lower, and turn huge and very heavy molds entirely by myself.

My molds don’t look particularly elegant, but they fulfill

their functional purpose. One disadvantage of using handmade molds is that they

are often quite cumbersome. When they are filled with liquid clay, they become

very heavy and difficult to lift, turn, and hold in position for several

minutes when the clay needs to be poured out. For instance, my biggest plaster

mold weighs a fair amount on its own and holds three gallons of liquid clay. So

it is completely beyond my strength. For this reason, I was forced to devise a

hoist system in my basement for the excessively heavy molds. I screwed a hook

into the ceiling and attached a chain hoist to it. This allows me to lift,

lower, and turn huge and very heavy molds entirely by myself.

Sometimes I substitute the press-molding

technique for slip-casting. I press clay into a plaster mold to create certain parts

to be used in my project. However, this happens quite rarely.

I have always tried

to ensure that all my processes (including the preparatory ones – developing

ideas, sketches, and so on) don’t take years of effort, as they often do with

real masters of art. And I have never devoted as much attention to detail as I

have observed some of my colleagues at the Summit studio doing. I saw girls

there make a mug on a pottery wheel and put it under plastic to keep it moist

through the week. A week later, after careful contemplation, they would attach

a handle to the mug and once more put it under plastic. After another week and

more pondering, they would adorn the mug with a floret. Yet a week later – one

more floret. All that irritated me. I have always tried to do everything fast,

in one go, although such haste has not always been advisable.

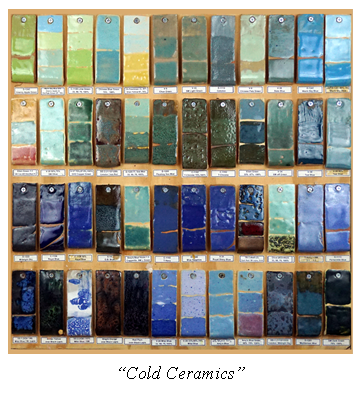

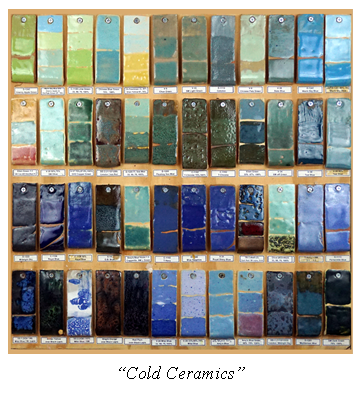

On one occasion, my teacher, Carole, suggested that I test

glazes before using them on my ceramics. “Life is too short for that,” I told her.

In response to which I immediately received a slap on the forehead. Although ten

years after that episode, I realized I had been wrong. So I made two boards with

testing plates – one in cold, and the other in warm colors. Each plate I made contains

two, and sometimes three or even four color tones. Having such boards has turned

out to be very beneficial, and now I don’t understand how I was ever able to live

without them.

On one occasion, my teacher, Carole, suggested that I test

glazes before using them on my ceramics. “Life is too short for that,” I told her.

In response to which I immediately received a slap on the forehead. Although ten

years after that episode, I realized I had been wrong. So I made two boards with

testing plates – one in cold, and the other in warm colors. Each plate I made contains

two, and sometimes three or even four color tones. Having such boards has turned

out to be very beneficial, and now I don’t understand how I was ever able to live

without them.

* * *

People often ask where I get the ideas for my ceramic works and

for my paintings. Sometimes they also inquire how I come up with the colors.

And this certainly does not come as a surprise. Occasionally I get similar

questions regarding my literary works. As soon as one of my books gets

published, I immediately face inquiries about the origins of its plot. So how

do I respond? Naturally, I admit that I don’t come up with all the plots on my

own. Then where do I get them? The answer is pretty obvious. I borrow the plots

for all my books from Pushkin. But this applies only to the books I have

written in Russian. Some of my works have been translated into English. Where

do I get the plots for these? Here too, the answer is pretty obvious. The plots

for these, naturally, come from Shakespeare.

How do I respond to questions about the origins of the subjects

and colors in my ceramic works and paintings? Of course, I don’t come up with

these on my own either. I get every single one from Leonardo da Vinci. And I

believe my replies sound natural and expected to those who asked.

But on a serious note, I would like to mention two sources that

really did inspire me to create two series of artworks. The first was the

extended series of variations Picasso painted in 1957 based on Diego

Velázquez’s 1656 work, “Las Meninas.” As soon as I saw a couple of

reproductions of these “Las Meninas” after Velázquez, I decided to create

variations of my own. Soon after, I created my work in oil called “Boy on a

Cube, after Picasso.” Then, for a long time, I forgot about the idea of the variations.

I recalled it only when I started working with ceramics,

after I came across a number of these variations in the Picasso Museum in

Barcelona. That’s how a series of four ceramic

plates came about: “Requiem for Guernica, after Picasso”; “The Cow with the

Subtle Udder, after Dubuffet”; “Construction Workers – Adam and Eve, after

Leger”; and “Military Violinist, after Chagall.” And

just recently, another ceramic plate came into being –

“Las Meninas, after Velázquez.”

The second source from which I drew inspiration was the rock

art of native Americans. I have a series of plates I made under the influence of

the rock art of American Indians. This influence lasted for a long period of

time.

* * *

My earlier experience with painting led me to recognize that a

two-dimensional environment was too tight for me. My hope was that ceramics

would provide me the opportunity to transcend two-dimensional limitations.

However, it turns out that even my sculptural ceramic works seem less than

three-dimensional, though my plates, which are supposed to be flat, are

definitely more than two-dimensional. So ultimately,

I ended up considering myself a two-and-a-half-dimensional ceramist.

* * *

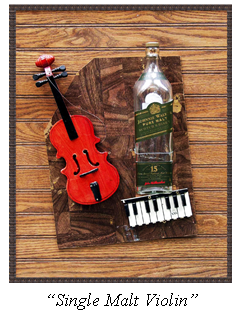

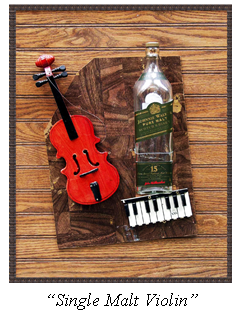

Another of my art pursuits is creating collages. At some

point in my life, I started to favor Scotch whisky over all other strong

alcoholic beverages. And the type that increasingly appealed to me the most was

single malt whisky. The price of these precious drinks turned out to be lower

than I expected. To commemorate the inarguable triumph in reaching this